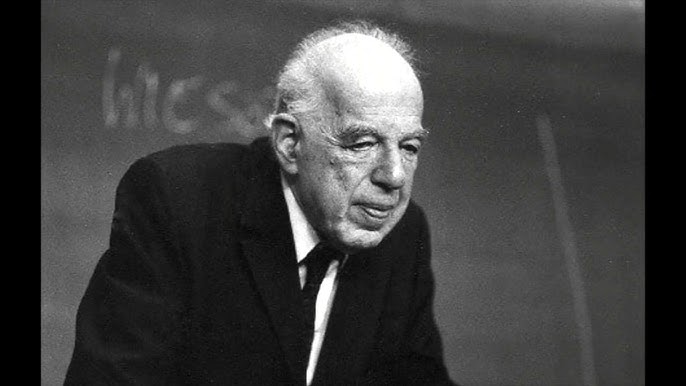

Rethinking René Wellek: On Destroying Literary Studies (1983)

August 9, 2025

René Wellek's essay, “Destroying Literary Studies,”¹ was published in 1983. This period was marked by the widespread dissemination of post-structuralism, deconstruction, reception aesthetics, and reader-response theory within literary departments across Europe and America. As Reingard Nethersole's research points out, 1983 was not only the year of Wellek's critique but also the year Edward Wadie Said's influential essay collection, The World, the Text, and the Critic, was published. Nethersole suggests that this year marked a critical juncture where the state of martial law in literary theory—a term used by opponents to describe the excessive dominance of certain theoretical perspectives like post-structuralism and deconstruction in critical discourse—was being questioned and re-examined.²

In his article, Wellek reviews the system of literary studies—supported by the three pillars of theory, criticism, and literary history—that had gradually formed since classical antiquity and was institutionalized in the nineteenth century. He posits that this structure faced systematic erosion from within the discipline itself. First, he criticizes the trend of denying the aesthetic properties of literature and equating it with all forms of writing. This "prison-house of language" theory, developed by figures like Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man, led to the denial of the self and the connection between literature and reality, encouraging critics to replace the understanding of works with language games, thereby blurring the line between criticism and creation. Second, he opposes the tendency to abolish textual authority and the ideal of correct interpretation. While acknowledging that reception aesthetics and reader-response criticism rightly draw attention to the reading process and the history of readers, he argues that in their extreme versions, such as those of the Constance School and Stanley Fish, they risk devolving into relativism and subjectivism, even advocating that interpretation creates the work. Wellek insists that despite ambiguity and indeterminacy, context and tradition can still set limits for interpretation, and this pursuit is the core driving force of literary studies. Finally, he critiques the devaluation of the evaluative function. He argues that both the systematic indifference of structuralism and the politicized criticism that dismisses value judgments as "elitist" ignore the unavoidable role of evaluation in selecting canons and defining traditions. Even popular literature can be distinguished in quality, and its opponents are, in fact, also making value judgments. At the end of the essay, Wellek clarifies that he is not against theory; on the contrary, he had introduced and developed literary theory and acknowledged the value of structuralism in fields like narratology. However, he rejects nihilism and linguistic isolationism, advocating for the complementarity of theory and criticism and the joint defense of aesthetics, interpretation, and evaluation, warning that the entire edifice of literary studies would otherwise collapse in self-deconstruction.

In fact, the very context of this article's publication—in The New Criterion, a journal known for its conservative stance and anti-theoretical posture—is itself significant.

However, Wellek's influential essay has also been subject to reflection. For example, in a 1996 paper studying the academic discourse on the "death of theory," Jeffrey Williams³ provides a detailed tracing and examination of the "anti-theory" wave that included Wellek's article. Williams shows that this rhetoric of "endism" or "catastrophism" often serves to re-establish the legitimacy of a certain critical discourse (such as a return to historicism or ethical criticism). He argues that these were sometimes a conservative counterattack against the radicalization of critical discourse in the 1970s, aiming to weaken the central position of theory and cultural studies in literary criticism, and were closely related to academic and economic power struggles within universities. He criticizes this narrative for creating an illusion of a sudden rupture, concealing the continuation and transformation of theory. For instance, the concerns of deconstruction (instability of meaning, textual self-referentiality, etc.) have seeped into New Historicism, gender studies, cultural studies, and other fields, but the "end of theory" discourse obscures these continuities to legitimize new or old discursive centers. Most importantly, Williams also reminds readers that this discourse is often accompanied by political and cultural appeals to "return to common sense" and "rebuild consensus"—which undoubtedly reverts to a top-down elitist notion.

Indeed, many of Wellek's criticisms in the article can be seen as lacking rigorous argumentation. For example, his critique of Derrida's texts as "at most, displays of intelligence and wit" now appears to be an unreflective and undefended reiteration of the principle of representation. Similarly, when he cites the absurdity of Hamlet being seen as a woman in disguise, it is a perspective that fails to anticipate how contemporary British Shakespearean theater companies have long extended their own lineage and context to embrace such provocations through reinterpretation. On the one hand, Wellek appears to subscribe to a form of authorial worship, where the critic's task is consequently reduced to excavating the truths that the artist, for various reasons, left unsaid. If this were truly the case, the logical step would be to urge artists to exhaustively explain all their great ideas before they die, rendering criticism obsolete. On the other hand, when Wellek claims there is "an insurmountable gulf between great art and utter trash," this risks lapsing into a pedantic cliché, lacking further justification. Who is allowed to write the enduring canons? Are some "low-brow popular works" actually the products of compromise under creative constraints? Is the catalog of the canon negotiable and therefore shaped by power? These questions, raised since the rise of postcolonialism and feminism, remain blind spots in Wellek's essay—for instance, not a single female or non-Western literary work appears in the entire article.

To expand on this point, it is worth considering the reception history of Wellek in China. His book Theory of Literature has long held a pivotal position in university department curricula, providing a clear and operational disciplinary framework. It responded to the aftereffects of the preceding politicized discourse, but more so, it also established a certain disciplinary regime. Compared to the later influx of post-structuralism, deconstruction, and cultural studies, it was more inclined to maintain the autonomy of the text and the continuity of the canon, naturally remaining wary of theories that emphasize difference, power, and discursive construction. Coupled with a series of Wellek's sometimes overly aggressive critiques, including this essay, which were selectively absorbed into the domestic discourse as arguments for "anti-nihilism" and "anti-relativism," the academic community found greater discursive justification for keeping radical methods at bay. It is worth asking whether all of this contributed, to some extent, to a certain "anti-theory" trend.

1. René Wellek, “Destroying Literary Studies,” The New Criterion 2, no. 4 (December 1983).

2. Nethersole, Reingard. "Chapter 2 Theory Policing Reading or the Critic as Cop: Revisiting Said’s The World, the Text, and the Critic." In Policing Literary Theory. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2017.

3. Williams, Jeffrey. “The Death of Deconstruction, the End of Theory, and Other Ominous Rumors.” Narrative, vol. 4, no. 1, 1996, pp. 17–35.

All Rights Reserved © Juntao Yang