Disempowered Women in Discursive Articulation: The Beautiful Legend of Typhoid Mary

September 2, 2025

Seemingly disparate meanings, symbols, and identities are always articulated into a discursive whole within specific contexts, thereby achieving a certain stability—what she "is," what she "did," and "why" she did it. Articulation,¹ as Stuart Hall argues, is not natural or inevitable but a temporary linkage forged within power relations. To put it simply, it can be understood as an adhesion, like glue, or an assembly, like piecing together Lego bricks.

An elaborate strategy of stigmatization is always adept at articulating itself with expressions of truth that are less easily questioned, in order to steal a portion of their symbolic authority. For instance, when a woman is found guilty of murder by a court, the ensuing tabloid gossip will splice judgments and representations about her onto the legal verdict: she is either cast as an unchaste woman or depicted as a wicked mother who abandoned her family. Numerous stigmas attach themselves to the truth statement of the "judicial verdict," sharing its authority and ultimately congealing into a discourse of stigmatization. Thus, what was originally a simple factual denotation like "she murdered" is rewritten as "she murdered because she is a low-life," "her unchastity led her astray," or "her crime is the bitter fruit of all women who reject the patriarchal family." Yet, the prejudice does not become true in the process.

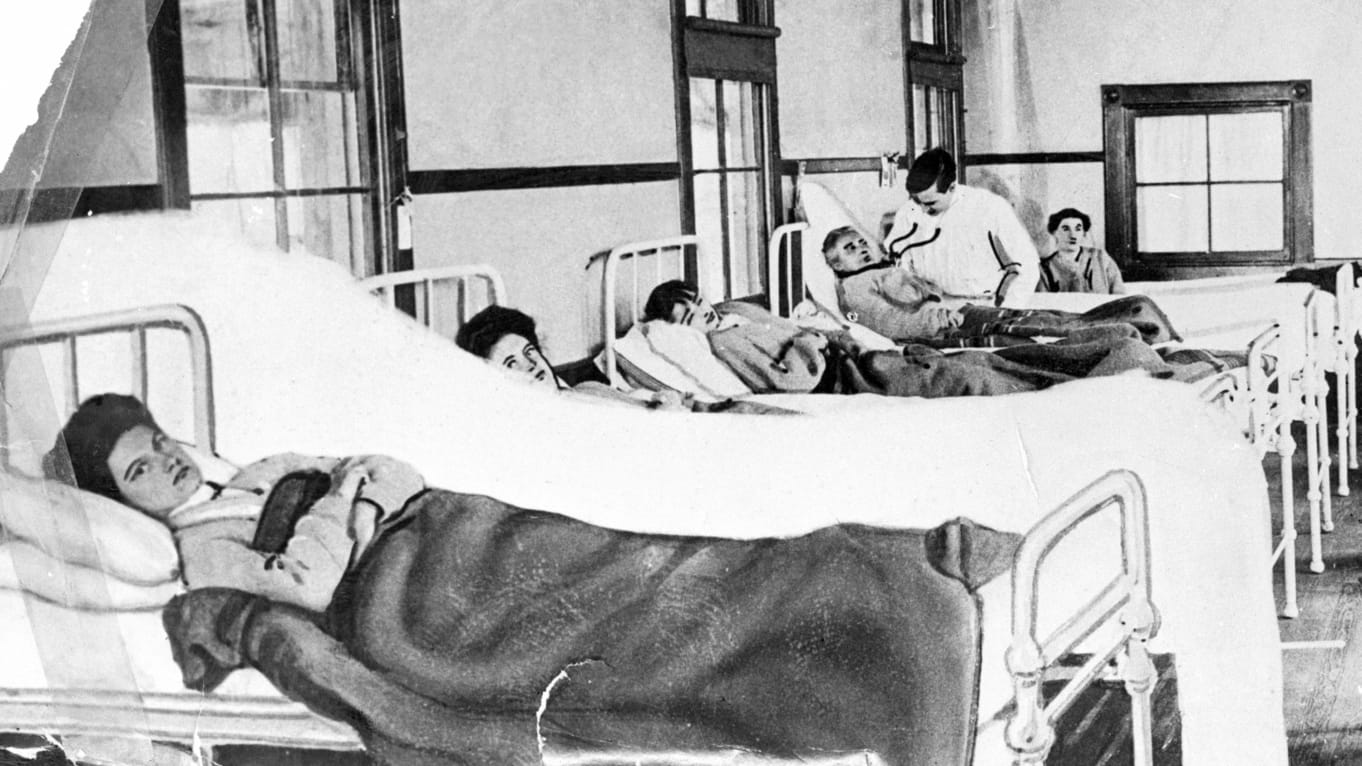

This mechanism constantly reappears in history and the present. Priscilla Wald² examines the story of "Typhoid Mary": an Irish immigrant woman, an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid, and an employed domestic cook. In an era that did not yet understand asymptomatic transmission, she unintentionally infected and caused the deaths of many people while working as a cook in various places. After an investigation, she was forcibly quarantined in laboratories and even a mental asylum. After some time, she was released upon swearing an oath to never cook again. However, her new job as a laundress could not provide a living, forcing her to resume cooking under a pseudonym. After causing another outbreak, she was finally captured and isolated on an island for the rest of her life. Mary became the perfect vessel for prejudice. As Mani Othman and William W. Darrow³ note: her identity as an Irish immigrant worker confirmed the imaginary of being "dirty and infectious," which in turn reinforced stereotypes about immigrant laborers; her status as a single, masculinized woman allowed tabloids to portray her as an unruly, and even deliberate, murderer spreading germs. In fact, George Soper, the sanitary engineer who first tracked her down, proposed to her during her quarantine and was rejected—a detail that was surprisingly used as further proof of her incorrigibility. Typhoid was objective medical evidence, but the prejudices surrounding her did everything possible to cling to it, borrowing its authority. Through meticulous fabrication and sharp malice, the mechanism of stigmatization was thus built around a supposed truth, and she ultimately became a "cultural carrier."

Echoing the ordeal of Typhoid Mary, the film Malèna (The Beautiful Legend of Sicily) also reveals this assembly mechanism of stigmatization. Isolation and poverty compel Malèna to use her body to survive during the German occupation, a forced survival strategy that the townspeople quickly frame after the war as irrefutable proof of her being a "slut" and a "traitor." A woman's sexuality and the imaginary of national chastity are woven into the same discourse, making an individual's act of survival seem to naturally transform into a symbol of collective shame. The townspeople's political anxieties and male desires intertwine, using a few seemingly minor facts to sustain a grand moral narrative, sealing one person's fate as an outlet for collective revenge. The public head-shaving and beating in the streets at the film's end is not just the climax of violence but also a visualization of this process of articulation: society uses the ritual of punishment to confirm and reproduce the truth it has constructed for itself.

1. Stuart Hall, “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10, no. 2 (1986).

2. Priscilla Wald, “Cultures and Carriers: ‘Typhoid Mary’ and the Science of Social Control,” Social Text 52/53 (1997).

3. Mani Othman and William W. Darrow, “The Wall, the Ban, and the Objectification of Women: Has ‘Uncle Sam’ Learned any Lessons from ‘Typhoid Mary’?” International Journal of Social Quality 9, no. 2 (2019): 1+. https://doi.org/10.3167/IJSQ.2019.090202.

All Rights Reserved © Juntao Yang